- Home

- Robert Pascuzzi

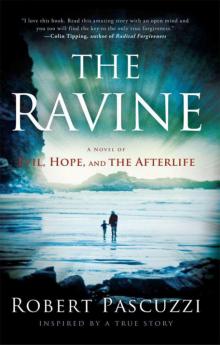

The Ravine Page 9

The Ravine Read online

Page 9

When they got to the car, Mitch said, “Whew, I hope I didn’t say anything too stupid. Your dad just looked at me and didn’t say anything, but I think your mom liked me.”

Carolyn laughed and said, “He liked you. If he didn’t, you would have known.”

That night when she came home, her father was sitting on the porch, waiting up.

“Hi, Dad, what are you doing up so late?”

“Waitin’ for you. I wanted to tell you something. That fellow, Mitch, do you like him?”

“I really do, Dad. I think I might actually love him.”

He looked at her and smiled. “That’s good, because I stayed up tonight to tell you I think he’s a keeper. He seems like a fine young man to me.” That was all. With that he got up and walked into the house and up to bed, and Carolyn watched his rocking chair sway to and fro until it stopped.

She looked up at him now and waited, hoping he would encourage her and Mitch to wait to speak with the boys.

Joe wasn’t given to needless sentiment, but he was in foreign territory and knew bad news didn’t get better with age. “I don’t think it’s going to get any easier in a few days, and it’s possible they will find out from someone else.”

Mitch agreed. “Honey, we’ll speak with them tonight after dinner. They’ll know something is up anyway, and we’ll be in Akron at least until Monday.”

Joe and Rosemary decided it was time to let Carolyn and Mitch be alone, and so they hugged them and said good-bye at the front door. Fortunately the boys could stay with their grandparents while Mitch and Carolyn were gone, and they would know how to handle their concerns.

Mitch and Carolyn looked at each other across the table. “As usual, your dad gave us some good advice,” he said. She nodded. “I mean about praying for guidance,” he added.

“Mitch, I’m not ready to talk to God just yet. Can you do it?”

Dinner was an odd affair, and as Mitch suspected, the kids knew something was up. Luke, their eleven-year-old, noticed his mom had been crying, and asked her why. She tried to put him off by saying it was just the change in seasons, and her allergies were acting up, but at dinner when Carolyn suddenly excused herself, the pretense started to crumble.

“Dad, what’s going on? Are you and mom getting a divorce like Tommy’s parents?” Luke asked. He looked like he was on the verge of tears.

“No, son, nothing like that. Let me get Mom, so we can have a chat.”

Mitch knew the moment had finally come, and said another silent prayer for God to put the right words in his mouth as he went to retrieve Carolyn. Their three boys thought of Danny and Rachel more as a big brother and sister than as friends. Heck, they even called them by their first names. Rachel and Danny had insisted on that. And Evan and Christopher were like family as well. You couldn’t be closer without being blood relatives.

Carolyn was in the upstairs bathroom. Mitch could tell that she was inconsolable. It broke his heart to do it, but he tapped on the door and told her it was time to talk to the kids. They couldn’t wait any longer. Carolyn walked out, nodded bravely, and said, “Tell me one thing, Mitch. How, just how, do you tell your children one of their friends is dead, and that he was murdered by his father, who also killed his wife and then committed suicide? None of this makes sense, even to an adult, let alone to three small children.”

“I don’t know. But we’ll do our best.”

When they sat down at the kitchen table, all three boys were wide-eyed and clearly frightened. Their nine-year-old, Joey, thought for sure Mrs. Furlong had called his mom like she said she would if he got out of his seat one more time, and six-year-old Frankie thought they were going to have to move because one of the kids in his kindergarten class had to move and he was crying about it all that morning. Frankie didn’t really know what “moving” meant, but he knew it wasn’t good, and he hoped that wasn’t why his mom and dad looked so serious.

Luke was just confused and worried.

“Listen, boys, we have some really bad news we have to tell you,” Mitch started, “and, well, there just isn’t any easy way to say it.” Uncharacteristically, the three boys were silent. Carolyn’s sobs were the only sound in the otherwise silent room.

Mitch took a deep breath to steady himself and said, “Danny, Rachel, and Evan died today.”

Now that it was out there, the news was greeted with a chorus of confused questions all around the table. Frankie started to cry; then the other two boys followed suit. Finally, Luke turned to his mother for confirmation and said, “Mom, is Dad right? Are they really dead?”

“Yes, I’m afraid it’s really true.”

“What . . . what happened?” he replied as his lip started to quiver.

Carolyn wished for any other answer than the one she had to give. A plane crash, car accident, house fire, even that they were murdered by some stranger—as awful as all of those explanations would have been, they paled in comparison to the truth. But she and Mitch had agreed they owed their children the truth. She tried to be honest while she softened the blow, but there really wasn’t a way to sugarcoat the reality regardless of what she said, so she told them in as few words as possible.

“Danny was sick,” she began. “I mean sick like in his mind, and he shot Rachel and Evan, and then he was so sad about what he did that he killed himself.” Once again, Carolyn had the sense that someone else was talking while she was saying these things, that she was watching herself sitting at the kitchen table telling her children this horrible news.

It took almost a half hour of answering questions, hugging, and crying, and then all five of them curled together on the couch and held each other. After a little while, they all sat quietly; even little Frankie (who was known for talking nonstop) was speechless, because words were inadequate at that moment. Eventually, the family headed upstairs to go to bed.

Finally the boys climbed in their beds, and said their nightly prayers. Each asked God to bless the souls of Danny, Rachel, and Evan. When it was Frankie’s turn, he looked at his father who was kneeling beside him.

“Dad, is it okay to ask God to forgive Danny for what he did?”

“Sure it is, son. We know that with God all things are possible, and Jesus died for all of our sins, so we can all be forgiven.” He sounded to himself a little like a preacher reciting something of which he was trying to convince himself.

“Okay, then . . . God, I know Danny did a really bad thing today, and I don’t know why he did it, but I hope that when he tells you he’s sorry, you will forgive him and let him go to heaven. Amen.”

Mitch averted his eyes while he pulled the covers around Frankie and kissed him on the forehead.

While Carolyn and Mitch dressed for bed, they made small talk about how exhausted they were and tried to feign a conversation that was in the realm of normal, reaching for any topic other than the black cloud that had descended upon their home that day. Both in their private thoughts were grateful this horrible day was finally coming to an end, but dreaded the night and what lay ahead in the days to come.

They settled their heads on their pillows, but through the silent language of old friends, agreed they were not yet ready to turn out the light. Sleep was not likely to come to either of them, despite the fact they were entirely spent, so they lay there for several minutes, simply holding hands, staring at the ceiling, and waiting for the pain to subside. But it didn’t.

Just as Mitch reached over to turn out the light, he noticed Luke standing at the door. His two younger brothers then appeared behind him and they stood in a cluster. Each clutched his respective pillow, blanket, and favorite stuffed animal. With the innocence, honesty, and wisdom that only children possess, they had devised the best and perhaps only plan that would allow their family to navigate the darkness and safely arrive at daybreak.

The oldest brother, Luke, spoke for all three: “Mom, Dad, can we sleep in here with you tonight?”

CHAPTER 8

Reality

Grief teaches the steadiest minds to waver.

—Sophocles

MITCH DIDN’T MAKE it to daybreak. He awoke a little before five, while it was still dark outside. Once the ugly reality settled in, he knew sleep was out the question. He silently grabbed his sweats, stepped over the boys, and crept down to the kitchen. Sleep, blessed sleep, was a gift on this day, so the last thing he wanted to do was to wake anyone prematurely. He was grateful for the rest he did get, because he expected the day ahead would be emotionally grueling. In this instance, ignorance was bliss. Mitch didn’t know how right he was about the day to come, nor did he realize that the reality of yesterday’s events was far worse than had yet been revealed.

He curled up in his favorite easy chair and sat quietly with a glass of orange juice, gazing through the sliding glass doors. Little by little daylight overtook the night. He hoped Carolyn would sleep in a bit, not only to spare her a few moments of pain but to give him a little time to sit alone and consider the jumble of facts that were plaguing him.

He was an architect by training, and so his initial instinct was to evaluate a project and try to figure out how it all fit together. A magnificent bridge was worthless if it couldn’t support the weight it was intended to carry. As a child, he would spend hours building a structure out of blocks, and then slowly add more and more blocks, one at a time, until it inevitably came crumbling down, determining the load-bearing weight. Everything had a breaking point, a threshold. It was just a matter of how much weight or pressure was applied, and eventually it would collapse. So he looked at yesterday’s revelations in much the same way, and was utterly confused. This felt more like a massive collision than a trickle, but what did he really know? And why hadn’t he seen it coming? Had he just been too preoccupied with his own life to notice anything? With something so monumental brewing, how could he have been so unaware?

He prided himself on being observant. He paid attention to the little things because they were often indicators of major issues lurking just below the surface. These habits showed up in the way he raised his children and managed people, and in his keen ability to read the body language of a client or, more importantly, smell that a junior architect might have cut corners or been a little sloppy. Buildings needed to survive all eventualities, not most eventualities. When they didn’t, disasters could occur—not the time to discover a structural problem. So Mitch generally followed his sniffer and, if something was amiss, he usually uncovered it.

The more Danny’s actions sank in, the more confused he became. There were dozens of unanswered questions. He presumed he would get some clarity later today when they met at Tom Schroeder’s house, but he just couldn’t push away the image of Danny shooting and killing his wife and child. It was just too horrible to contemplate.

Unfortunately, Mitch knew that murder-suicides were all too common. The ritual was for television reporters to flock to the crime scene like jackals to prey, poke a microphone in the mouth of a hapless neighbor or relative, and probe for answers about the personality of the murderer. The public demanded to know “why.” Everyone longed to uncover the motive, as if there would be one singular “ah-ha” moment that would explain why an otherwise loving father and husband would commit such a heinous act. Invariably, the bewildered individual would respond along the lines of “he was a nice guy, I never would have expected him to do something like this,” which was not terribly comforting for the populace at large, because it meant that your next-door neighbor or perhaps even your Uncle Dave might be capable of the same sort of violence and was worthy of suspicion. However, had Mitch been asked about Danny, he certainly would have said he was baffled by the situation, and probably would have defended him until all the facts were known.

Twenty-four hours ago he believed Danny and Rachel had a typical suburban marriage. There were hints of trouble, but nothing major. He thought back to the last time he had seen them, two weeks ago in Cleveland for dinner at their favorite Italian restaurant, Johnny’s Bar on Fulton Road.

It was just the four of them that night. Carolyn and Rachel focused on each other, their conversation jumping back and forth breathlessly, while Mitch tried to coax an unusually quiet Danny into opening up. Sports seemed to be about the only safe topic, and on that subject, Danny could astutely analyze the last Browns game or rate the depth of the Indians’ bench. LeBron James was the topic of conversation for most of the night. Hopes were high for the Cavaliers with this nineteen-year-old phenom. Finally, Cleveland was getting some respect. Mitch loved sports as well, but had begun a period of self-exploration in the last several years that he felt had been instrumental in his growth as a father and a husband and had contributed to his success in business.

He had read dozens of books in his exploration of spiritual matters and the connection between personal satisfaction, spiritual growth, and achieving one’s full potential. There was no doubt in Mitch’s mind that this pursuit had allowed him to overcome barriers in all aspects of his life. He had always felt that the best self-help book ever written was the Bible and that, for sheer simplicity, there wasn’t a better guide to living than the Ten Commandments. Faith was the bedrock of his existence, and he tried to follow the section in the second chapter of James, about how “faith without works is dead,” to combine the spiritual with the practical.

However, when he was in his thirties, he purchased a Tony Robbins book after seeing him on a television show. At first he was put off by Robbins’s excited attitude, but after listening for a few minutes, he started to understand that this person was sincere, and really excited about life.

It wasn’t long before he’d purchased the CD program and then parted with a few thousand dollars to attend two seminars. He found them to be life-altering. One process in particular made a great impression on Mitch. He discovered he could walk across hot coals without experiencing pain or burning his feet! Even after he did it, he still thought it might be a hoax, so he volunteered to place the coals for a group later in the day, and discovered it was totally legitimate. After that, he gave up some of his skepticism and cynicism, and he began to recognize the self-limiting beliefs he carried around subconsciously. He started to see that what looked impossible often was very possible. And he wanted to share this newfound knowledge with his friend.

About a year ago, Mitch purchased tickets for Danny and one of his buddies to attend a Tony Robbins seminar when he was appearing in Cleveland. After Danny went, he called Mitch and thanked him for the tickets, but told him he hadn’t gotten much out of it because he already knew most of the stuff they had presented, and he didn’t see any reason to explore self-improvement because he was pretty happy with the way things were. Mitch got it. Some people didn’t want to be bothered challenging themselves, and some of the concepts in the program were meant to force oneself to confront uncomfortable truths. It wasn’t for everyone.

After his stint in jail, Danny’s life had gone pretty well. He had a wonderful wife and two beautiful sons, and Maryann had become a devoted a daughter who completed their family unit. He was able to move to a comfortable house in Akron largely because his brother worked so hard to expand his small chain of sporting goods stores into fifteen locations.

Danny had a great gig managing a region that included five stores, which also gave him plenty of freedom to spend his days as he liked. Sometimes that included a round of golf in the afternoon, and sometimes it meant shacking up with a woman he’d met on the road. Despite the fact Danny wasn’t known for his work ethic, Tony didn’t seem to mind, and paid him handsomely.

Danny went to church regularly with his family, as did Mitch, and he and Rachel even attended a Bible study with Mitch and Carolyn, but they rarely had anything to say at those meetings. Every once in a while, Mitch would bring up God, and Danny would evade the question or just change the subject. He just seemed like a happy-go-lucky guy.

It was true that Rachel had found out about one of the girlfriends, and that seemed to be a bone of contention. A few sum

mers ago both families rented a house for a week on Put-in-Bay. They arrived on Saturday; then, on Monday afternoon, after Danny and Rachael returned from the supermarket, Danny announced that he had a problem at work and had to head back to Akron that night. Rachel didn’t seem pleased, and on Wednesday she decided to return. There seemed to be a problem, but neither of them talked about it.

Thinking back, Mitch could see the invisible moat drawn around his friend that was intended to keep people at bay. Rachel and Carolyn seemed to be able to explore their most personal matters, and their bond was immovable. Yet Carolyn hadn’t a hint from Rachel that there were any serious problems, or at least nothing she had shared with Mitch.

Now he felt guilty because he had to admit he had allowed his relationship with Danny to drift apart after they moved to Akron. The last time they’d spent any real time together was when Danny came over and helped Mitch build a deck. That was the sort of guy Danny was. He would never turn you down even for something as unappealing as deck building. In that respect he was a true friend. If you were in a foxhole, Danny was the guy you would want next to you.

But thinking back on that hot summer day, after they had finished the deck, and were sitting on it having a few beers, he remembered a comment Danny made in passing.

“You know, Mitch, sometimes I wish I had it all to do over again.”

“What do you mean? Your life has gone pretty well.” Mitch presumed Danny was making an oblique reference to his time in jail, but knew enough never to specifically refer to that topic.

“It’s just about freedom, man. You know, being able to do what you want when you want to, not being tied down all the time.”

“Whoa, dude, do I hear a midlife crisis coming on?”

The Ravine

The Ravine